The past few weeks have been a good reminder that I can still contribute to projects, as a patient partner, in meaningful ways. This involves quite a bit of adaptation from the ways in which I used to do things, because I’m now living with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to my rare disease.

That’s in addition to its usual symptoms of constant and severe pain in the affected area, in my case the right hand and lower arm. Along with problems with the joints of each finger as well as my wrist, changes in skin temperature, an extreme sensitivity of the skin… there are a whole slew of symptoms of this bizarre and rare condition.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is an odd beast of a disease, considered to be both an autoimmune condition and a neuro-inflammatory disease. That accounts in some ways for the range and diversity of its symptoms, although it doesn’t explain why each patient with CRPS tends to have a different set or severity of symptoms.

I only found out a few months ago that MCI isn’t uncommon among patients with long-term CRPS, although no one had mentioned this possibility to me – until I began experiencing it.

Perhaps my physicians hadn’t want to worry me with a symptom that I might never have to deal with. One thing is certain; had I known about the possibility, I’d definitely have been very worried about it…

Research has shown that many people with permanent CRPS have difficulty with “naming/declarative memory”(1), which is where I now have the most trouble. I now often use the wrong word, in conversation or in writing, when I’m certain that I’ve used the correct one…

The best, or worst, example is still the time I walked around a funeral saying “congratulations” instead of “condolences” – while I was absolutely certain that I was saying “condolences”!

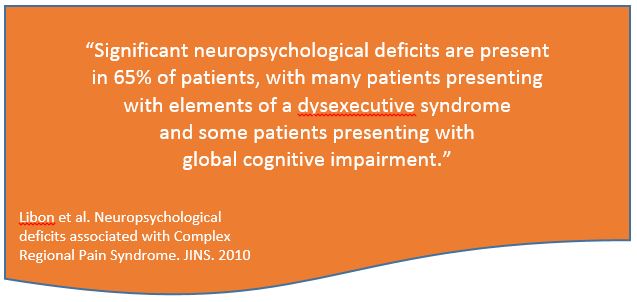

Significant neuropsychological deficits are present in 65% of patients, with many patients presenting with elements of a dysexecutive syndrome and some patients presenting with global cognitive impairment.”(1)

Libon et al. 2010. JINS.

Although I remember how to do things – riding a bike, driving, baking cakes – I might forget why I went somewhere, or what it is that I’m supposed to be doing at any given time. Smartphone reminders are a huge help with this!

My smartphone holds daily reminders to eat lunch, for example, because my neuropathic pain often interferes with my appetite. Without a reminder alarm I would often forget to eat, and then wonder why I had a headache by dinnertime.

I also have issues when it comes to concentration, to being able to focus on something for more than an hour at a time. Even this blog post! It will probably take me several separate 45- to 60-minute blocks of time to write this, spaced throughout the day, so that I can let my brain ‘rest’ between sessions.

That’s one of the adaptations I’ve had to make, to be able to participate in projects as a patient partner, despite MCI. I can’t focus on anything for more than an hour, and sometimes not even for that long; after that, I need to do something that I would have called ‘mindless’ in the past.

These ‘mind breaks’ might be making my lunch, going for a walk, or washing dishes, or just watching the birds enjoying themselves at the feeders in our backyard.

I’ve had to learn that my brain needs these breaks, that stopping in the middle of something isn’t a ‘waste of time’. It has become a survival mechanism, so I’ve adapted to it. Again, I use my smartphone calendar as a tool for this; if I need two hours to read a patient-centric project report, I schedule two or three separate sessions into my calendar – with reminders! – on the same day. Interspersed with mind breaks, of course.

As difficult as it is, emotionally, I’m also very upfront with project organizers about my MCI. It’s only fair to tell them that I can’t handle meetings or teleconferences that last more than an hour, otherwise I’ll lose the ability to follow along – let alone provide any meaningful patient suggestions or insights.

If that doesn’t fit within their plans, I’ll suggest that they find another patient partner; sometimes I can recommend other individuals to them.

Finally, I have to make it clear that I now need days rather than hours to read or review a document; things that I used to be able to read in an afternoon now must be broken up into many one-hour blocks of time, with mind breaks in between. Sometimes, even after a few hours of rest, my brain still can’t focus again.

It’s not as though there’s a magic formula, such as “read for an hour, rest the brain for an hour”. That’s not how MCI works, not in my case at any rate!

Within these constraints, at the moment I’m a Patient Partner on two different projects. One is with the Pain Science Division of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association, and the other is the Play the Pain project. You might recall the Play the Pain team, from some of my posts last October describing a two-day series of creative workshops that they’d organized for chronic pain patients – along with researchers studying pain.

Let’s use the second one, for an example of how I’ve been able to adapt to MCI – at least enough for meaningful patient partnership in a couple of projects. Play the Pain is being run with government funding at Concordia University, through both its PERFORM Centre and its TAG (Technoculture, Art and Games) group within The Milieux Institute for Arts, Science and Technology. With collaboration from the McGill Centre for Integrative Neuroscience (MCIN). Sounds cool, right?

This FRQSC-funded project brings patients, scientists, designers and engineers together, to investigate the best ways to empower patients to assist in advancing medical sciences.”(2)

Media Health; Concordia University

The goal is to create a new game + research app, to be designed for chronic pain patients – with pain patients. It will be a “playful mHealth platform, designed to put chronic pain patients and their care givers at the heart of pain research.”(3) It aims to:

explore the ethical, practical and cultural tensions between lab-based research that focuses on medical conditions, versus data-driven research that focuses on self-monitoring and sharing of one’s living conditions through digital health frameworks.”(3)

Media Health; Concordia University

To account for my CPRS-related MCI, whenever I have a patient partner task, I first estimate how long it will take me to complete. Then, because I can’t predict when I’ll have a ‘worse’ day for concentration and focus, I double my estimated time.

Once I have an estimate of duration, I break the task down into one-hour blocks of time. I schedule each into my smartphone calendar – with alarms, otherwise I’ll forget! – adding mind breaks of at least an hour in between.

If the task involves any editing, I have to allow extra time to go back and re-read whatever I’ve done, because… I’ll forget what I’ve read and edited. That’s also how I write blog posts these days. I used to be able to sit down for an hour or two and write a good post.

Now I have to account for an inability to maintain focus on the details after an hour, a lack of concentration on a single task for long periods, losing my train of thought, etc. Oh, and that train of thought? The train never stops there again. Once an idea is gone, it’s gone.

I have to admit, I’m proud of myself. Not only for finding ways to adapt to the cognitive impairment – which I detest, by the way! – but for finding ways to do things that are meaningful.

I went into the field of biomedical ethics or bioethics out of a desire to help people, to help patients, and contributing to these types of projects as a patient partner allows me to continue doing that.

As always, thanks so much for stopping by! Stay tuned for more news and posts about these projects, and hopefully others once these two are finished. Feel free to reach out via Twitter or Instagram, because this blog has disabled comments to avoid hack-attacks from overseas. I really love hearing from you, though!

References

(1) David J. Libon, Robert J. Schwartzman, Joel Eppig, et al. Neuropsychological deficits associated with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J International Neuropsychological Society (JINS). 2010; 16, 566–573. Online 19 Mar 2010. doi:10.1017/S1355617710000214. Accessed 03 Jan 2020:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-international-neuropsychological-society/article/neuropsychological-deficits-associated-with-complex-regional-pain-syndrome/F56D83F23BB269C52DDF43198BA0536D#

(2) Research: Projects. Media Health; Concordia University [Media Health Lab is a collaborative initiative supported by Concordia University PERFORM Centre and The Milieux for Arts, Culture and Technology]. 2019. Online. Accessed 03 Jan 2020:

http://media-health.ca/projects/

(3) Play the Pain. Media Health; Concordia University [Media Health Lab is a collaborative initiative supported by Concordia University PERFORM Centre and The Milieux for Arts, Culture and Technology]. 2019. Online. Accessed 03 Jan 2020:

http://media-health.ca/play-the-pain/