It will be Rare Disease Day (1) in just over a week, on February 28th. This is important to me, because in early 2016 I was struck with a rare disease. And then misdiagnosed, over a period of almost three months.

That doesn’t seem like a particularly lengthy delay for a diagnosis, I know. That said, it was extremely frustrating to know that something was terribly wrong with me – and yet be unable to make myself heard. As a patient, and also as a bioethics professional.

Perhaps even more so on the bioethics side. Because each new tack I attempted with my local community hospital – requesting a change to a different specialist, a second opinion, a referral – was refused.

And at each interaction with my assigned specialist, there were instances of (albeit sometimes subtle) disregard, disrespect, and even overt flippancy. Towards me, as a patient; often with a family member in the hospital examining room. A witness.

Although I understood that the hospital’s refusals were unethical, if for no other reason than that they violated this institution’s own list of patients’ rights (2), I felt powerless. I was suffering from excruciating pain, unable to sleep or rest, and trying to manage a new department and team at work.

There was simply nothing else I could deal with, above trying to get through each day at work. At that point – undiagnosed and enduring agonizing pain – I found myself unable to fight for my own patient rights.

There I was, someone who’d spent a career in bioethics and patient protection, incapable of protecting my own rights. The irony wasn’t lost on me, but it took months – and finally a diagnosis – to be in a position to do anything about it.

Those feelings, of being incapable of claiming my own patient rights, led me to engage in patient advocacy and support activities. At an individual level, at which I feel I’m making a difference for other patients; people with the same disease, and in similar situations.

Part of these activities involve raising awareness of this medical condition, so that other patients can be diagnosed and treated more rapidly. Because aggressive treatment of this disease, within three months of onset, can resolve it.

Otherwise, as has happened in my case, it evolves and progresses into a painful, permanent, and debilitating chronic condition.

One major challenge, in raising awareness of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is nomenclature; its multiple names throughout the years.

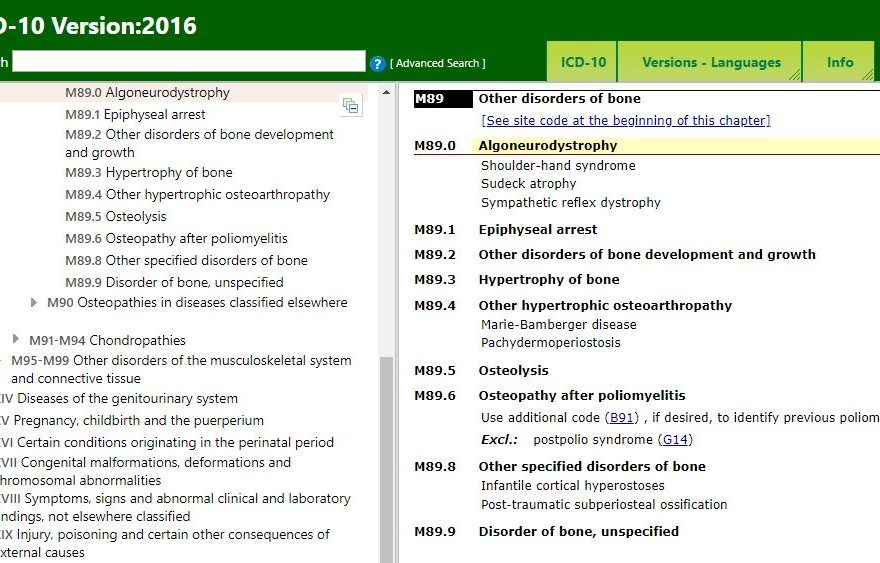

The 2016 version of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s ICD-10, for example, lists it not as CRPS but as “Algoneurodystrophy”. The ICD-10 also shows sub-categories, for “Shoulder-hand syndrome”, “Sudeck atrophy”, and “Sympathetic reflex dystrophy”.

The latter is actually incorrect, as the previous name for CRPS was RSD; “Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy”. For those of you unfamiliar with the ICD-10, it is the WHO’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision.

There have also been, over the years, other names used for this same rare disease. A compelling argument has even been made that these inconsistencies in nomenclature have had a negative impact on research and treatment of patients with CRPS.(4) That it’s long overdue that the field of medicine to:

put to rest not only the name, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, but the misguided theories, research, and limited treatment it spawned.”(4)

Coderre; Complex regional pain syndrome type I: What’s in a name?; J Pain; 2011

Those of us working in bioethics should already have a solid understand of the importance of language, of semantics. This situation, of issues which may have been caused – over a period of decades – by the inconsistent nomenclature of a disease, is likely new to some of you.

Whether communicating with patients and caregivers, or with physicians and other health professionals, we in bioethics can have a role in ensuring that – at the very least – everyone on a care team uses the appropriate nomenclature for a particular condition.

In the case of my specific disease, and “the bewildering symptoms observed in CRPS patients” (4), it’s important to avoid any additional confusion for patients – as well as for the healthcare team.

So if you happen to hear any of the outdated terms above, still being used, please ask that the current name for this rare condition be used instead: Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, or CRPS.

Thanks for stopping by the blog, and for reading this post!

References:

(1) The European Organisation for Rare Diseases (Eurordis). “Rare Disease Day”. Online. Accessed 17 Feb 2018. Web:

https://www.rarediseaseday.org

(2) “Resources available to the community: Your Rights as a User”. Service Quality and Complaints Commissioner of the Montreal West Island Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre (MWI IUHSSC). Online. Accessed 17 Feb 2018. Web:

https://ciusss-ouestmtl.gouv.qc.ca/en/users-info/users-rights/service-quality-and-complaints-commission/#c36732

(3) World Health Organization (WHO). Eds: Heads of WHO Collaborating Centres for the Family of International Classifications. “International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision” (“Official Update to the published volumes of ICD-10”). Oct 2016. Online. Accessed 17 Feb 2018. Web:

https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en#/M89.0

(4) Terence J. Coderre. “Complex regional pain syndrome type I: What’s in a name?”. J Pain. 2011 Jan; 12(1): 2-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.001. Online. Accessed 17 Feb 2018. Web:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4850066/