I first met the neuro-anesthesiologist at 1115 on a Friday morning, for what was supposed to be a consultation to confirm a suspected diagnosis. He was squeezing in my consultation between his surgeries, so his secretary sent me to meet with him in the hospital’s pre-operative and post-operative area (pre-op and post-op).

By 1215 – an hour later! – he was wheeling me into the day surgery operating room (OR) himself, during his lunch break. This was completely unexpected. I’d taken an early lunch from my own job, expecting a very brief meeting with this specialist. So I had driven myself to the hospital, planning to be back at work by noon.

For months all the problems with my hand and wrist had been ignored or dismissed by the orthopedic surgeon who’d been assigned to me by the hospital, so I wasn’t expecting any action to be taken so quickly.

To start, this neuro-anesthesiologist asked me sit on a gurney, in one of the more secluded and private bays of the pre-op/post-op area. So that no one would overhear our conversation, my personal health information. He pulled over a plastic visitors’ chair, and sat down on it beside my hospital bed – rather than standing over me.

Next he pulled the over-the-bed-table in front of his chair, and set down his notepad, pen, and phones. That created the feeling of a desk between us, a physical separation. From my usual bioethics perspective, I thought this was a good patient-centric start to our consultation.

Then he sat back in his chair, looked at me, and took the time to introduce himself. He explained his background and training, why he thought he might be able to help me. I think that was a first for me, for specialists at that specific hospital at any rate.

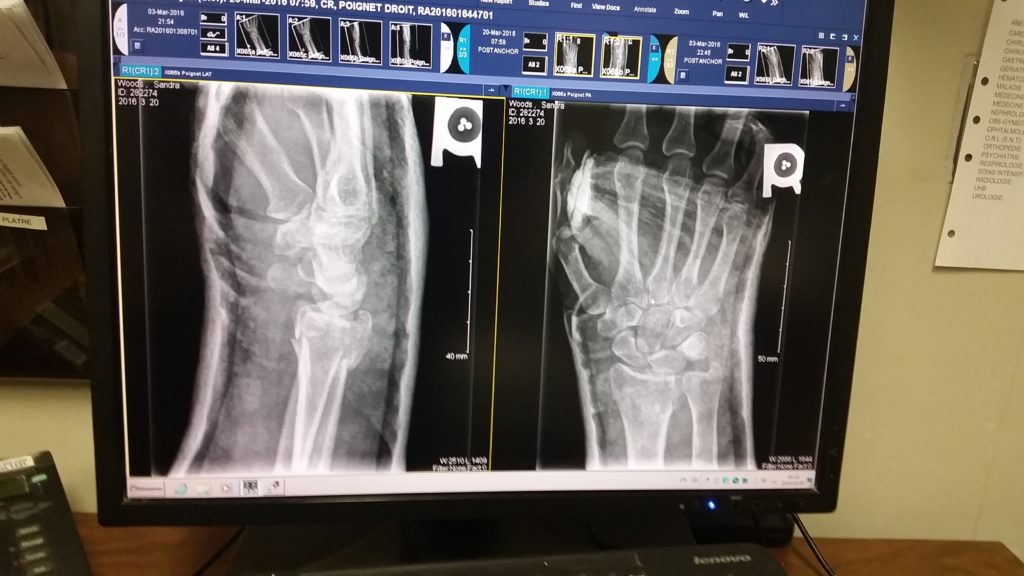

Only then did he take my full medical history, writing copious notes, and examine me. We went over the details of the fracture that had triggered all of the hand and wrist problems I’d been having for months. He also asked me a lot of very detailed questions about the types of pain, joint issues, and other symptoms I’d been having since I’d broken my wrist in early March.

When he asked whether I was able to work despite all of these symptoms – particularly the elevated pain level – he seemed quite surprised when I replied that I was actually at the hospital on my lunch hour. He inquired about the type of work that I do, so I happily explained that my field is bioethics and that my background’s in clinical (medical) research ethics.

We spoke for a few minutes about that, and my own experience working as part of a hospital research team. He asked whether I was able to understand – and feel comfortable – when physicians speak “medicalese”, because of my clinical research experience.

I replied that I understood quite a bit of the “secret language of doctors”(1). He seemed to get a kick out the fact I used to proofread medical journal articles, for post-doctoral students on a medical research team.

Because of this, he offered to speak to me the way he’d speak to a nurse; but only if I’d promise to ask him about anything I didn’t understand or wasn’t sure about. I was touched. This specialist was offering to tailor his approach – and his terminology – to me, to make me more comfortable.

That patient-centered, tailored, offer went a long way to making me feel that I was a partner in my medical care, and it set the stage for me to be fully involved in decisions about my treatment. It created a healthcare environment in which I wasn’t having decisions made around me, but rather with me.

I learned first-hand that the patient-centric approach that we promote in bioethics can make an enormous difference in how a patient may perceive their entire healthcare experience. It took only a minute for this clinician to ask a couple of general questions about my educational and employment background, to try to evaluate my level of health literacy, and to offer an approach that he thought would be appropriate.

I ended up spending quite a bit of time in this OR, with this neuro-anesthesiologist, so I later asked him whether he did this with all of his patients. He told me that he’d started to tailor his approach to his patients’ level of medical knowledge 15 or so years earlier, when he found out after a surgery that one of his patients had medical experience himself.

I can’t overstate how important that approach was to me, at that point in my new patient journey – as a rare disease patient. After months of having my symptoms dismissed and ignored by another specialist physician, my neuro-anesthesiologist made me feel like a partner in my own medical care. It also turned out to be beneficial to him in several ways!

Because he’d shown this openness to engage with me as a patient, when he asked about the onset and progression of my symptoms I mentioned that I had photos on my phone; of different clinical signs of the disease over the months. He asked whether I’d be willing to show them to him, and to walk him through the disease progression with my photos. He told me it was rare to be able to see the earliest onset of clinical signs of this disease, and that this would be very helpful for him.

After we’d spent a half-hour in this consultation, he leaned forward in his chair, took a deep breath, and said; “I’m sorry to confirm that you have Complex Regional Pain Syndrome, what used to be called Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy. The photos you’ve shown me confirm it without a doubt, there’s no need to do any additional evaluation or testing. But I’m going to do my very best to help you – you’re in good hands.”

And just a few minutes later I was in the day surgery OR, for the first of 6 medical procedures he’d perform for me within 10 business days, to try to stop the disease from spreading any further than it already had.

How was this beneficial to this specialist physician? I’ll write about that tomorrow – stay tuned!

References:

(1) Goldman, Brian. The Secret Language of Doctors. Harper Collins

Canada. 29 Apr 2014. ISBN: 9781443416016. Information about this book is

available online at:

http://www.harpercollins.ca/9781443416016/the-secret-language-of-doctors