I’d broken my right arm (fractured my radius; a Colles’ fracture) in early March 2016, and had gone to a local community hospital. The emergency physician there had done an excellent job of setting it; I know, because she proudly showed me the before and after X-rays!

While she’d evaluated me, we’d been chatting about bioethics (or medical ethics) – my field. She knew that I was interested in what she was doing, from the perspective of a fellow healthcare professional. She explained her process in detail; it was a relatively quiet night in the emergency department, so she could take the time to do this for me.

When I left the emergency department I was told that the hospital’s orthopaedic team would call me within a few days, to book an appointment for an outpatient follow-up. This would probably be about 10 days post-fracture.

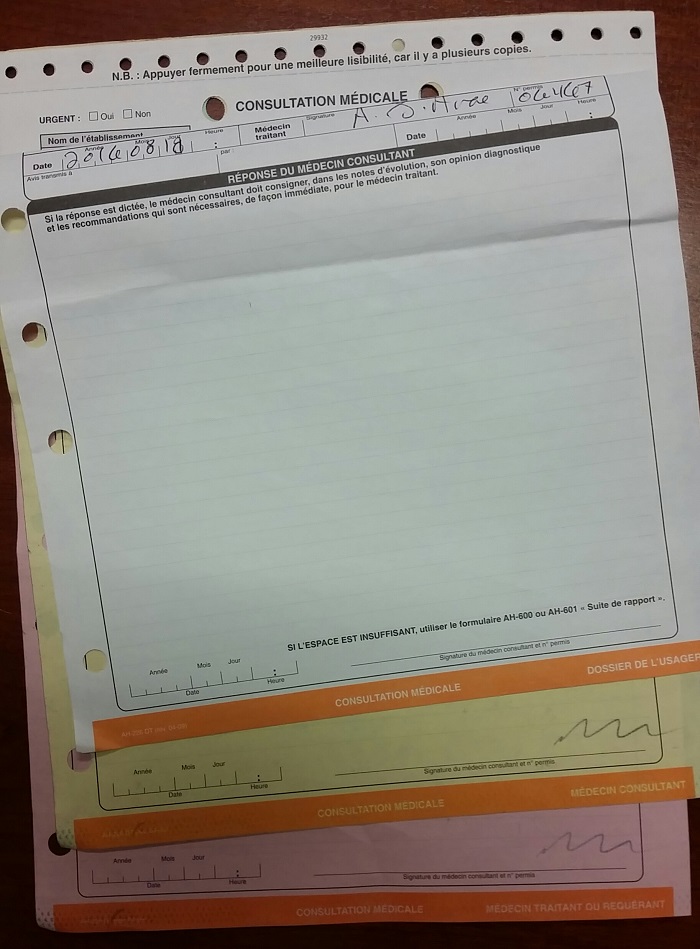

Luckily I was given a copy of the referral form; a carbonless paper, or NCR, form. After 5 days I hadn’t had a call to scheduled a follow-up, so I called the orthopaedic department myself. Good thing I called; it turned out that somehow my referral form had been lost, within the hospital.

Because the healthcare system in Québec is operated by the provincial government (including hospitals), and paid for with taxpayer funds, we lack a functional electronic medical record (EMR) or electronic health record (EHR) system.

This means that our healthcare institutions still function largely using fax technology to communicate patient information. My American friends will have difficulty understanding that I was asked to fax my referral form, from one department in the hospital to another department – at the same hospital!

Sadly, as I’ve posted on multiple other social media – from a bioethics viewpoint – this is largely how Canadian healthcare works. Or doesn’t.

Because of the heavy snow and extreme cold during our winters, I hadn’t been able to get out on my bicycle for a few months. I wanted to be sure that my hand and arm were ready to start cycling as soon as possible after the cast was removed, so I’d already scheduled physiotherapy (PT) appointments.

Like most people, though, I don’t have a fax machine at home. I called my PT clinic to explain the situation, and they kindly offered to fax the form to the hospital for me. I’m not sure what patients who don’t have access to fax machines are supposed to do in these types of situations; drive to the hospital to hand-deliver the form? Or use a carrier pigeon?

Once my PT clinic had faxed the referral form, I quickly received a call from the orthopaedic department and was scheduled for a follow-up appointment in mid-March. I was assigned to an orthopaedic surgeon, even though it didn’t seem that I’d require surgery; the hospital assigns physicians in this department on a rotation basis, and he was the next in line.

When I met with the orthopaedic surgeon, he advised me to sleep with my cast raised on a pillow, and to keep my arm on my desk at work, because my fingers seemed swollen. He also advised me not to hold my arm in one specific horizontal position, because doing so could cause the not-yet-set fracture to change positions.

My husband and I were going on vacation for a week, so I was prescribed some pain medication – in case the pain bothered me while we away. The surgeon then asked the orthopaedic nurse to remove my cast, so that I could walk over to the radiology department for an un-casted X-ray.

I was told to then return to the examining room, to wait for the surgeon to receive the new X-ray. At least the radiology is computer-based, not faxed from one hospital department to another!

The surgeon explained that he wanted to ensure that the fracture was healing properly, and that the two edges of the bone were still aligned in the correct positions.

The X-ray showed that the bone was healing well, and I was relieved when the surgeon confirmed that I wouldn’t require surgery. At this point, I was feeling rather pleased with the way things were going.

It wasn’t yet certain whether I’d need to wear a cast for 6 or 8 weeks, but I’d probably be out on my bike a couple of weeks after the cast came off. If I was riding again by April, I wouldn’t miss too much of our short cycling season. My husband was sitting in a guest chair, and gave me a thumbs up; everything seemed to be going so well.

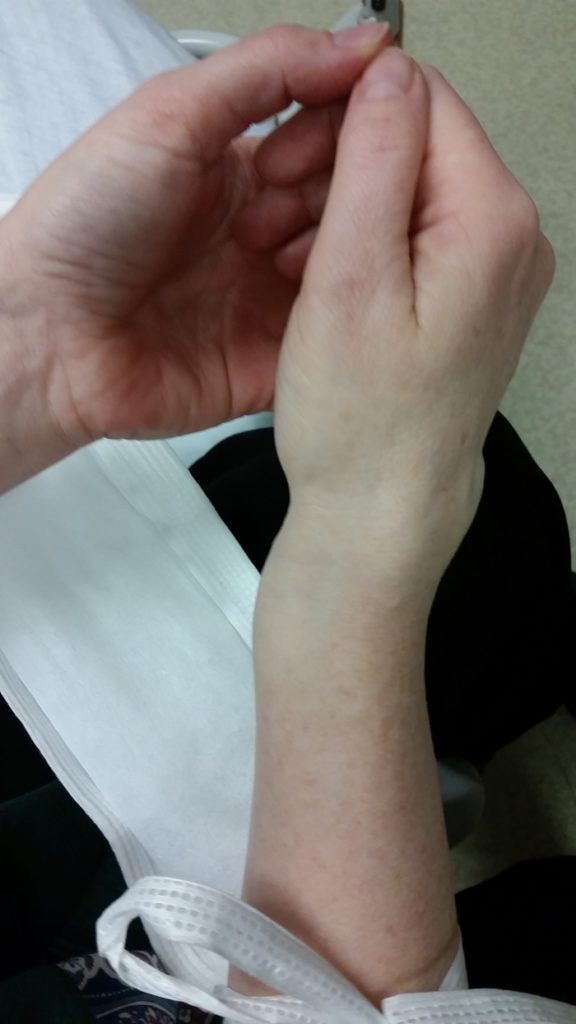

The orthopaedic nurse returned to the examining room, and began to recast my arm. The surgeon went to consult with another patient in an adjacent treatment room. I noticed that the nurse was holding my arm in the exact position that the surgeon had just told me to avoid.

When I mentioned this to him, he replied (in French) that he knew what he was doing and that he handled fractures just like this one all the time as a he specialized in orthopaedics.

At that point I felt an unbearable pain, and one of my legs started to shake violently. I had no idea what was happening. The nurse looked down at me, as I sat huddled on a gurney in excruciating pain, and told me (in French) to “stop exaggerating ma’am, you’re not a child”…

My jobs, for years, have involved protecting patients’ rights – yet I was unable to utter a word in response to his unacceptable comment. It was so inappropriate that I was completely stunned. My husband later told me that he’d been furious with the nurse, but hadn’t said anything because he didn’t want to interfere with my care.After a moment the pain subsided somewhat, and the nurse was able to finish casting my arm.

After a moment the pain subsided, just a touch, and the nurse was able to finish casting my arm. Before we even left the hospital, the pain had come back in full force, and I had to sit down as a wave of nausea washed over me.

I was in so much pain that I thought I was going to be sick, right there in the waiting room. The nurse had said that pain was normal during re-casting, so I thought the pain would subside after a little while.

It never did…