The word ‘pain’ is all around me, every day, and I just noticed it. It’s on billboards and in flyers, in grocery stores, newspapers, and restaurants. It even shows up on the side of city buses!

Not because of advertising for pain medications, or raising awareness for chronic pain diseases, but because it’s the French word for bread.

I live in Quebec, near Montreal. The provincial laws here require that in signs and advertising, French can be used along with English or another language, as long as the French text is clearly more predominant.(1)

The phrase more predominant usually means that the French version is at least twice as big, or takes up at least twice as much space, as the other language.(1) But for many types of signs, only French can be used; for example, advertising on buses and on some large billboards.(1)

So just imagine that everywhere you see the word bread written down – in shops, on menus, in advertisements on the side of your bus – I see the word pain! It’s really kind of funny that I’ve never noticed this before, given that just over a year ago I was diagnosed with a rare chronic (neuro-inflammatory) pain disease.

This language law might seem odd to you, but it gets even stranger, particularly from a patient perspective. Quebec’s Charter of the French Language became law on August 26, 1977, but it’s most often referred to as Bill 101; the name of the legislation before it was became a law.

In these next quotes, “anglophone” means English-speaking, “francophone” means French-speaking, and “allophone” is someone who primarily speaks any other language. These terms were coined to avoid confusion between language and a person’s nationality or country of birth; i.e. English for someone from England, and French for people from France.

One of the things this law did, immediately in 1977, was to legally require the working language of the province to be French. If an English speaker owned a family business, the goal of this law was to force the owners and employees to all speak French – even among themselves – within the workplace. Due to public outcry, and the threat of civil rights lawsuits, the law wasn’t applied to very small businesses.

The contentious piece of legislation would pave the way for the francization of the province’s government, businesses, workplaces and education system…

At the time, many English-speaking Quebecers felt unwelcome in their own province, leading to a mass exodus of anglophones.

Many allophones (people whose first language is neither French nor English) also left.(2)

As an example, I’ll take my own family in the 1970s. Only my parents remained in Quebec; all of my parents’ 4 siblings, and their children, moved to Toronto or Vancouver. My grandparents and their many siblings also moved away with their families, from the city in which they’d all met their spouses and built their lives; only one of my great-aunts remained in Montreal.

Many years later, my father calculated that our family had ‘lost’ over 50 family members to other cities; all because of a law that made anglophones feel unwelcome in a city in which they’d spent their lives and been productive, and tax-paying, citizens. Many of my friends’ families up and left completely, leaving no one behind.

French instantly became the “official language of business, government, commerce and the courts. Immigrants would only be able to school their children in French, including out-of-province Canadians moving to Quebec, and commercial signs would be in French only… The law clearly, clearly, established the fact that we were now second-class citizens. Without Bill 101, Montreal would be an English-speaking city predominantly right now.”(3)

How does this impact patients? Canada’s publicly-funded healthcare systems are run by the individual provinces and territories, so Quebec’s hospitals – and most other healthcare facilities – are operated by the provincial government. Under this law, French instantly became the “official language” of healthcare here.

At first, patients thought that changes for healthcare would affect only the people working within governmental clinics and hospitals. That doctors and nurses might have to fill out administrative forms in French instead of in English.

But this law was applied on a much larger scale; to group homes, local community [health] service centres (CLSCs), rehabilitation centres, residential and long-term [nursing] care centres (CHSLDs), and youth protection centres. As well as to all organizations which enter into contracts with any public healthcare institution.

And patients themselves were singled out: English-speaking Quebecers have a legal right to receive health and social services in English. But this right is not absolute: there are limits to this right.(1)

Read that last sentence again. In Canada, we have a province in which English-speaking patients lack the rights to receive healthcare services in English. As an example, let’s look at patients’ own medical records (emphasis added):

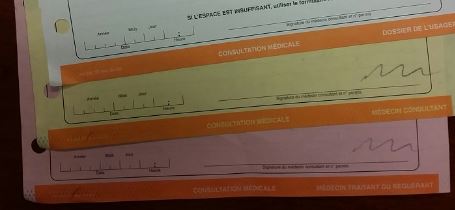

There is no right for patients to have their health and social services records (files) in English.

The general rule is that the person preparing a document for this kind of record, such as a doctor, can decide whether to write it in English or French.

However, a health or social services institution does have the option of requiring documents to be written only in French.”(1)

So any English-speaking patient can request their medical records, but then receive only French documents – and that’s legal here. The patient would have to pay out-of-pocket to have the documents translated into English, which would require that they hand over their sensitive personal information to a stranger – a translator.

In another example, hospitals and other healthcare organizations providing direct care to individuals can send patients to another region, use technology or interpreters to provide services in English, or have specific and restricted time-slots for providing services in English.

In the event that a patient requires emergency surgery, or have cancer, a hospital can decide to simply send them to a completely different region of the province – just to receive service in English. Right here in Canada.

And in my final example, you might wonder why some institutions have signs and posters in both English and French, while others post them only in French. Institutions can only have signs and posters in English if they are a “designated” institution…

In other words, the majority of the people served by the institution speak a language other than French. Designated institutions must still have French on their signs and posters along with English.”

This means that if an anglophone or allophone patient happens to visit a hospital that’s not one of the very few “designated institutions”, the information signs on the walls won’t even be printed in English. And no employee would be required to respond to them in English; under the law, it’s acceptable to hire only French-speaking employees. In hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, etc. In Canada.

This ends my little story; Bread, pain, patients’ rights.

References:

(1) Éducaloi. Language Laws and Doing Business in Quebec. Éducaloi [a registered charity, receiving some governmental support, providing information to citizens on legal rights and responsibilities]. On-line. Accessed 27 Aug 2017. Web:

https://www.educaloi.qc.ca/en/capsules/language-laws-and-doing-business-quebec

(2) Laframboise, Kalina. How Quebec’s Bill 101 still shapes immigrant and anglo students 40 years later. CBC News. 26 Aug 2017. Web:

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-bill-101-40th-anniversary-1.4263253

(3) Valiante, Giuseppe. After 40 years of Quebec’s Bill 101, its legacy is still a matter of perspective. The National Post. 25 Aug 2017. Web: