This isn’t going to be another blog post about COVID-19 statistics, I promise! There are already plenty of reliable sources of information out there for this pandemic situation. One great example is a new website that was quickly created by the Government of Canada.(1)

It groups all national information, recommendations, and resources into one place; including the numbers of current confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases under investigation in each province.

Because healthcare in Canada is administered at the provincial level, the actual COVID-19 testing, procedures, and treatments fall under the aegis of provincial health authorities. At a more local level our cities, towns, and villages can also make individual public health decisions.

It’s in this realm that the City of Montreal has really stepped up, making difficult decisions to protect our citizens. We were the first location in Canada, for example, to temporarily ban public gatherings of 250 or more people.

Montreal was also the first major city – at least in Canada – to close all municipal arenas, community centres, cultural centres, libraries, etc.(2) Although I’m not Catholic, I was pleased when Quebec’s Bishops decided to cancel all masses for the time being.(2) This measure was implemented to protect the predominantly elder populations of their congregations.

These types of public health interventions will not only protect our citizens, they’ll also help protect our healthcare professionals. The fewer people who contract COVID-19 – or seasonal influenza for that matter – the fewer contagious patients will require treatment from our nurses, physicians, technicians, and all the other individuals working in healthcare.

Are you wondering, at this point, why I said this wouldn’t be a post about COVID-19 statistics? I want to talk about this pandemic at a more personal level, based on my experiences as a bioethics professional and as a rare disease patient.

First off, my background includes a stint working with an epidemiology team. We were part of a university’s multi-hospital research centre, under the School of Public Health within the Faculty of Medicine of the university.

From there, I moved to management of a research ethics board (REB). These bodies are called institutional review boards (IRBs) in the US, and may go by different names in other countries. Between this, my other experiences, and my education, I have a decent grasp of healthcare here in Canada.

I was working at the hospital during a city-wide outbreak of a new strain of C. difficile, which was later termed an epidemic.(3) It causes ‘leaky’ intestines and resulted in severe diarrhea. There were 7,000 patients infected – and 600 fatalities – from this strain of Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) between April 2003 and April of 2004, across ten hospitals here.

As you can imagine, everyone working in the hospital was provided with information and training on how to prevent the spread of this infection. Some of the lessons that I took away from this have carried over into my personal life, even all these years later. Into my current patient journey, as a rare disease patient.

In what ways? Well, I always carry two pens in my purse; a spare in case the first runs out of ink. Medical clinics and hospitals here are often still paper-based, and will ask each patient to fill in a form when they arrive. A receptionist will hand you a pen, and usually a clipboard with a blank form of some sort.

Have you ever seen anyone cleaning these pens? The clipboards? I haven’t – except during that c. diff outbreak. So when I went to a private medical clinic today, for a scheduled vaccination that couldn’t be postponed, I expected to see them using what I’ll call an ‘epidemic protocol’.

I was stunned when I saw how casually the clinic employees, even some of the nurses, were treating hygiene – after a global pandemic had been declared. Overall, I was in the clinic for an hour, including the fifteen minutes I had to sit in the waiting area after my vaccination injection.

There were patients in the waiting area wearing masks and coughing, so obviously there was a potential for COVID-19. Yet there seemed to be no precautions at all at the front desk.

When I arrived, a receptionist asked to take my health insurance card. I asked whether I could place it into the card reader myself, as it was within reach. She refused, telling me that she had to keep it until I had paid the fee after my vaccination.

I had been watching, and had seen that she hadn’t used the hand sterilizer after handling the previous patient’s card. She then tried to hand me a clipboard and a pen, neither of which seemed to be particularly clean.

With my dynamic splint on my right hand, I had an excuse not to pick up the clipboard; I filled out the form on the counter – off to one side – using my own pen. Once I’d completed the form, I pushed the clipboard back towards her with my elbow. She looked at me as though I had two heads.

Not once, in the entire hour I was there, did I see any of the reception staff wash their hands or use the hand sanitizer product they had behind the counter. She then clipped my health insurance card into another clipboard, which the nurse picked up in her bare hands before calling me into a treatment room.

The nurse went over my medical history, and then got up to go get the vaccination from another room. When she came back into the treatment room, she washed her hands. Very quickly, literally just a squirt of soap and then running one hand over the other. Nothing like the way the public is being told to our wash hands:

Step 1: Wet hands with warm water.

Step 2: Apply soap.

Step 3: Wash hands for at least 20 seconds (including your palms, back of each hand, between fingers, thumbs and under nails).

Step 4: Rinse well.

Step 5: Dry hands well with paper towel.

Step 6: Turn off tap using paper towel.”(4)

All I could see were the multiple failures of basic practices to prevent the spread of infectious disease – by healthcare employees! From the inappropriate handling of patients’ health insurance cards, to handing out re-used and non-sterilized pens and clipboards to us, to failure to practice proper hand hygiene.

It was so disappointing, from my bioethics perspective. This clinic, I thought to myself, could very easily become a source of contagion. All it would take would be one patient with COVID-19, and the clinic’s own employees could end up spreading it to so many others.

I tried to raise my concerns with the receptionist as I paid my bill, and asked to see one of the supervisors for a moment. She told me that they were all ‘at lunch’, and I didn’t press it. But I couldn’t remain quiet about this, so here I am.

As with my last shingles vaccination (there are two different injections for the protocol my family physician chose for me, several months apart), I began to feel quite ill soon after the shot. Once I’m feeling better, I’ll call one of the supervisors; I picked up on her name from a conversation among employees.

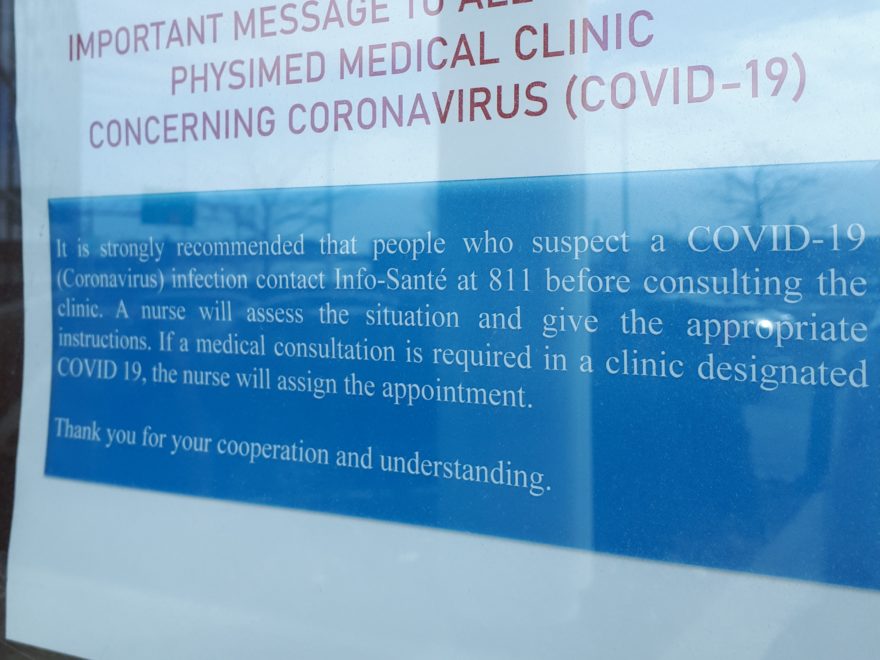

Hopefully she’ll at least listen to my concerns, to my descriptions of what I saw taking place at this health clinic. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with this image from a hospital I visited earlier this week – for an appointment related to my rare disease ‘-)

Oh, and do you remember what I said about my health insurance card? That it was handled by someone who hadn’t washed or sterilized her hands between patients? When she gave it back to me, I asked her to place it on the counter.

Then I pulled an alcohol wipe from my pocket and used it to pick up my card. I wiped it completely clean, even its edges, before I put it back in my wallet. All the while, she was glaring at me.

References

(1) Government of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Accessed 12 Mar 2020. Online:

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.html

(2) Andy Riga. As it happened: Quebec starts shutting down to slow spread of coronavirus. Montreal Gazette. 12 Mar 2020. Online:

https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/live-updates-quebec-doctors-want-limits-on-travel-gatherings-to-curtail-covid-19

(3) André Picard and Rhéal Séguin. Quebec acknowledges C. difficile ‘epidemic’. Globe and Mail. Oct 21 2004, updated 21 Apr 2008. Online:

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/quebec-acknowledges-c-difficile-epidemic/article20436116/

(4) Government of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Reduce the spread of COVID-19 – Wash your hands. Accessed 12 Mar 2020. Online:

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/reduce-spread-covid-19-wash-your-hands.html