At lunchtime today I presented a virtual talk at the pain clinic of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC), here in Montréal. Unlike most of my previous talks about chronic pain, though, this one was for Pain Patients rather than for healthcare professionals or researchers, medical students or residents, graduate students or other health trainees.

This presentation was hosted by the Chronic Pain Peer Mentorship Program (CPPMP) at the MUHC, a wonderful initiative which matches trained patient-Mentors with Pain Patients to offer additionally weekly support – for about 3 months each. Usually held on ZOOM or another virtual meeting place, these 12 or so weekly sessions can provide tips for dealing with pain, give Pain Patients an opportunity to talk with someone who understands the challenges of living with persistent pain, or simply to provide support and listen.

The beauty of this program is that it’s up to the individual Pain Patient to decide what type of input, interaction, or support they want from their Mentor. For a person in pain who doesn’t know anyone else who lives with a pain condition, it can be such a relief to realize that they’re not alone – to be able to speak with someone else who understands what kinds of challenges pain can create in our lives.

Today’s talk was part of a series of presentations offered by Mentors within the CPPMP, so it was open only to active and former patients and caregivers within the pain clinic that serves this entire university hospital network. That’s why you didn’t see anything about it here on the blog, or over on my other social media; I couldn’t invite you, so didn’t want to publicize it!

As you might have guessed by now, I’m one of the Mentors within this relatively-new program, and the third one – if I recall correctly – to give a talk to other Pain Patients. The last of these presentations was on some personal Tips and Tricks for dealing with pain, developed by another CPPMP Mentor who is a former nurse and lives with daily pain.

I wanted to do something a bit different for my talk – for a specific reason. I’ve always dealt with adversity and even pain by joking about it; using humour whether camping in the rain or arriving at the hospital with a visibly broken arm. To me, with my background as a competitive athlete as a child and then as military reservist, humour is a healthy way to deal with challenging situations.

Yet I clearly remember being told a while back, by a nurse at a hospital outside the pain clinic’s hospital network, that: “It’s not healthy to joke about your pain”. That comment has remained lodged in my brain for several years, and runs counter to what I’ve read in some current research into humour as a pain management technique or tool. So when I was given an opportunity to choose the topic for my talk – that’s what I went with; Humour and Pain.

Humour isn’t for everyone, particularly not the ‘dark humour’ that I use so much, but it was important for me to reassure other Pain Patients that it IS a healthy response to pain; a good coping mechanism… Just in case they ever run into someone like that nurse who tried to tell me that humour was an ‘unhealthy response’ to pain. So I’m going to do the same for you!

If you’re a long-time reader of this blog, you won’t be surprised to hear that most of my talk was based on recent research findings. After so many years working in bioethics and healthcare research myself, my first reaction when preparing a talk is ALWAYS to look at the current research. It’s like with PowerPoint animations; I just can’t help myself.

The people participating in today’s event surely noticed that I ADORE PowerPoint. Probably a bit too much, really, and that’s likely an understatement! Put it this way; I was proud of myself for not setting up a PowerPoint animation on every single slide, that’s how much I love using this presentation-building software.

That might go back to my days doing officer training sessions in the Air Force Reserves in the late 80s and early 90s, when the only real presentation tools we had were acetates and overhead projectors (and maybe the occasional live animal as a teaching tool during wilderness training sessions!). Most of those ‘presentations’ were simply typed text on a sheet of acetate, often run through a photocopier, presented on a large screen. And ‘Woo Hoo’, maybe I’d be allowed to use some colour markers to draw onto the acetates – just to highlight certain points.

That was so dull, so truly boring. For the trainees, but also for me as a trainer. So once PowerPoint hit the market, I was hooked. Even with the old acetates, though, I’d try not to read from my slides, but instead to talk about them – maybe give an example, or paraphrase technical language into normal words.

I did that again today, mostly showing excerpts from research studies on my slides and then explaining the findings in lay terms; translating medicalese and research jargon into everyday language. And, of course, throwing in some humour with comics and visual jokes.

One of the effects of my own rare chronic pain condition is that I now live with a ‘mild cognitive impairment’ (MCI), which makes it almost impossible for me to remember the punchline of a joke while I’m telling it. So these days I tell people that “I’m not funny, but I try hard”, and then rely on visual jokes.

Like one of the visual jokes I used today, as a bumper-sticker style image on a slide: “I used up all my sick days, so I called in dead.” And all the movement and ‘bounce’ of my PowerPoint animations went well with the topic of today’s talk: “Humour and Pain”.

That ‘mild cognitive impairment’ (MCI) I mentioned earlier also makes it a challenge for me to give presentations of any sort. So I’m happy that this talk went relatively well today. Happy with myself, even though I forgot to mention some key points; like that I’d be sharing a plain-text version after the event, so folks didn’t have to read all the information on the slides, and that I’d include links to the research papers I was referring to.

Ah well, I did the best I could with the few ‘brain bits’ – or little ‘bitty brain’ – that I have left! As for the many animations – the movement and ‘bounce’ – on my PowerPoint slides, I think that all went well with the topic of today’s talk.

Are you wondering what kind of research I found, on chronic pain and humour? Good, ‘cause here it comes! First, though I want to specify that the kind of humour I was talking about was the kind that brings people together; like that old expression ‘Laughing with you, not laughing at you’:

rather than making a joke directed toward each other or teasing one another, the participants joke together about their own experiences and collectively share their experiences through humor”.

“Humorous interpersonal interactions about chronic pain provided a forum for social support-building… Humor was affiliative and built social collaboration, helping individuals to together make sense of their pain”. (1)

Like what I mentioned earlier, the type of humour that we’re looking at here – in terms of research – really is ‘laughing with you, not at you’. Another study noted that “humour has been studied as a way of coping with pain and the emotional distress produced by chronic pain conditions” and found that there benefits for “the use of humour and main variables such as anxiety”. (2)

Isn’t that cool? The coolest study I found, hopefully not sounding too much like a research nerd, involved elders living with chronic pain. With our ageing population, this kind of study has become increasingly important over the past few decades:

Older persons in a nursing home were invited to join an 8-week humor therapy program (experimental group), while those in another nursing home were treated as a control group …

there were significant decreases in pain and perception of loneliness, and significant increases in happiness and life satisfaction for the experimental group, but not for the control group.” (3)

In short, the elders who received humour therapy for persistent pain reported less pain and less isolation or loneliness – while also experiencing greater levels of happiness and life satisfaction. This is FANTASTIC! Of course, humour isn’t the same for everyone. Our brains can register humour differently, to start:

Because there are a lot of different types of humour — from word-play and self-deprecation to slap-stick and dark humour — the way comedies and humour register in our brain can vary, making the neuronal activity in response to it very complex …

multiple brain regions, including both cognitive and affective components, are involved in identifying the social disconnect that makes something funny.” (4)

I noted during my talk that there can also be differences in how specific groups view humour, sometimes along cultural lines. To paraphrase from an article last year, in Psychology Today (5):

- There are cultural differences in how humour is used and what is “funny”

- Some groups view ordinary people as funny, while others feel that humour is best left to comedians

- In some cultures, humour is often used to cope with stress and difficulties

- Different cultures use different types of humour, in different ways.

And for many marginalized communities, dark humour in particular is viewed as something that has been a coping tool for hundreds of years. One piece, written by an Indigenous Person, really struck me:

In spite of all that we’ve endured, when I picture my community, all I can think about are my aunties laughing; throwing their heads back, slapping each other’s arms, and cackling like hyenas.

Indigenous humour is dark. Some call it gallows humour, but whatever it is, it has been our key coping mechanism, helping us survive 500 years of colonization.

Indigenous people are masters at taking the hurt and pain that was dealt to us, laughing in the face of it, and weaving it into ridiculous comedy gold.” (6)

In terms of non-cultural differences in humour, those of us who’ve worked in healthcare or the military can all remember dark humour being used in ways that wouldn’t even make sense to people outside these types of roles. Research is showing, more and more, that this is true of patients as well. This study looked specifically at chronic pain patients, and found that:

gallows humor” is recognized as having therapeutic value, particularly when used by individuals facing trauma or challenging circumstances in health settings…

“In clinical contexts, such self-deprecating humor has been found to boost psychological well-being, despite its dark(er) content, suggesting it is adaptive in the pain management context.” (3)

As for that military humour I mentioned, it’s not limited to combat situations. Sometimes it’s simply the overwhelming amount of paperwork or eForms to deal with, or the often appalling food – particularly the IMPs (called MREs in the US)… I can recall hearing a comment, at a Canadian base, that: “The IMP omelettes were so bad that we used them for target practice – and the bullets bounced right off”. (An IMP is an ‘individual meal pack’, the same as the ‘meal, ready to eat’ term used by the American military.)

For combat and other highly dangerous situations, I liked this comment from journalist Carmen Gentile in a piece in Esquire magazine back in 2013:

As I learned over the years covering combat … humor – often dark, absurd, and/or twisted – is essential for the preservation of sanity at war.

Without it, the daily threat … would drive even the most hardened soldier around the bend.” (7)

On the healthcare side, the inimitable Dr. Brian Goldman, well-known here in Canada for his White Coat, Black Art medical show on CBC Radio One, noted that an “important purpose” of dark humour in hospitals is to help health professionals cope, when so many people around them “are in pain and suffering”. (8)

Back to research involving chronic pain patients, there seems to be a consensus among studies that:

Using conversational humor was a sign of social support and a coping mechanism to help participants understand and make sense of their chronic pain experiences and maintain interactional levity, despite the seriousness of the pain conditions they all lived with.” (1)

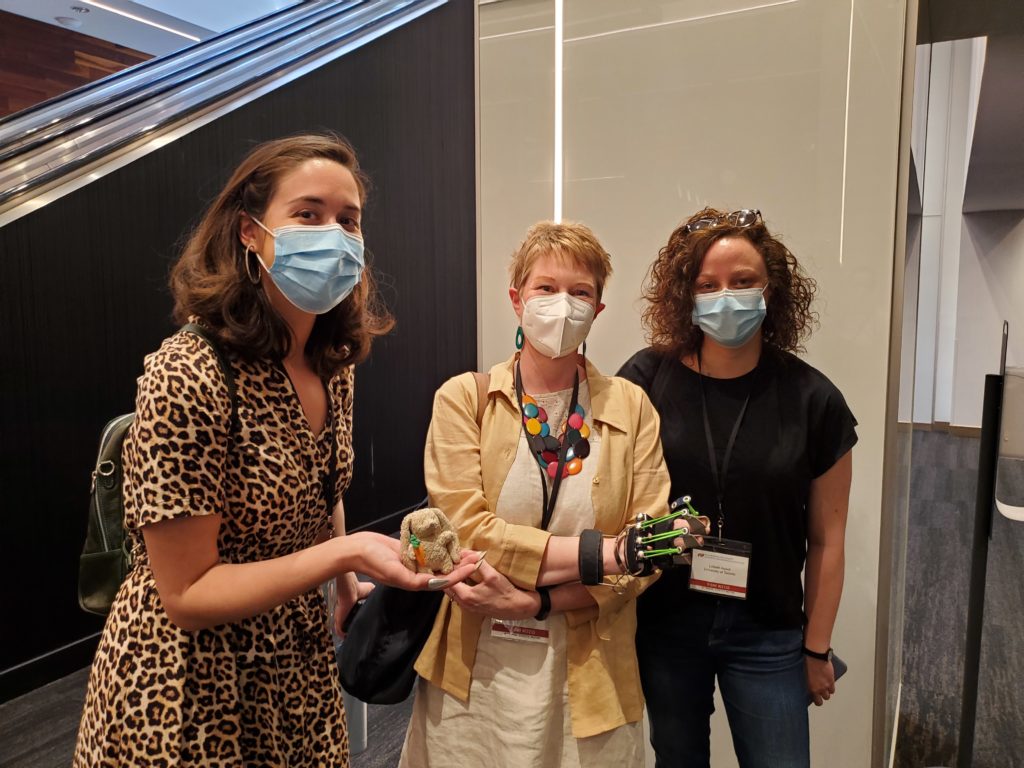

There had been comics and little jokes interspersed throughout my talk, and I closed it off with an appearance by Max; my little chronic pain and CRPS awareness buddy. He joins me for cycling, pain conferences and meetings, patient events, and more! Max is great at starting conversations and making connections, and he loves to meet pain researchers at events like the Annual Scientific Meeting of the Canadian Pain Society – where this photo was taken this past May.

This ended up being a much longer post than what I’d planned… One of the effects of the cognitive issues from my Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), that I have to just live with, is that I have trouble stopping once I begin to write. And my editing skills are shot all to heck.

Thanks so much, as always, for stopping by. The Comments feature became too much for my cognitive impairment to deal with a while back, so I’ve had to disable it. So feel free to reach out over on Instagram or Twitter (I’m hoping that the latter will survive that latest round of resignations after Elon Musk’s threatening emails to employees). Keep well, take care, and feel free to use humour to help you get through the day… no matter what it is that you’re dealing with these days.

References

(1) Finlay KA, Madhani A, Anil K, Peacock SM. Patient-to-Patient Interactions During the Pain Management Programme: The Role of Humor and Venting in Building a Socially Supportive Community. Front Pain Res. 2022. Online. Accessed 01 Nov 2022:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpain.2022.875720/full

(2) Pérez-Aranda A, Hofmann J, Feliu-Soler A, Ramírez-Maestre C, Andrés-Rodríguez L, Ruch W, Luciano JV. Laughing away the pain: A narrative review of humour, sense of humour and pain. Eur J Pain. 2019. Online. Accessed 01 Nov 2022:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ejp.1309

(3) Tse MM, Lo AP, Cheng TL, Chan EK, Chan AH, Chung HS. Humor therapy: relieving chronic pain and enhancing happiness for older adults. J Aging Res. 2010. Online. Accessed 01 Nov 2022:

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jar/2010/343574/

(4) Mutabdzija Jaksic V. Why watching comedies is ‘important medicine’: Psychologists dive deep into how watching comedy affects our brain, health and quality of life. CBC/Radio-Canada. 2020. Online. Accessed 21 Oct 2022:

https://www.cbc.ca/comedy/why-watching-comedies-is-important-medicine-1.5519839

(5) Hagan, E (Reviewer). Laughing at Different Jokes: Humor Across Cultures. Psychology Today. 2021. Accessed 24 Oct 2022:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/non-weird-science/202111/laughing-different-jokes-humor-across-cultures

(6) Devery Jacobs, 21 Jun 2021. LOLing Is Good Medicine: How Indigenous People Use Humour For Survival. Online. Accessed 12 Oct 2022:

www.refinery29.com/en-ca/2021/06/10477340/how-indigenous-people-use-humour-for-survival

(7) Carmen Gentile. Celebrating the Twisted Genius of Soldier Humor. Esquire. 2013. Online. Accessed 30 Oct 2022:

https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/news/a25928/dark-soldier-humor/

(8) Brian Goldman, MD. How Doctors Use Dark Humour to Keep Ourselves Going. HuffPost-BuzzFeed Inc. 2014. Online. Accessed 03 Nov 2022:

www.huffpost.com/archive/ca/entry/how-doctors-use-dark-humour-to-keep-ourselves-going_b_5368005