When you think about rare diseases, is it usually those affecting children that first come to mind? Genetic diseases like Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) or Phenylketonuria (PKU), pediatric cancers like Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Gliomas (DIPG); there are far too many rare pediatric disorders:

About 80% of rare diseases are caused by genetic changes.

25% of children with a rare disease will not live to see their 10th birthday.” (1)

Despite the fact that rare diseases are – in fact – rare, an astounding number of rare medical conditions have already been identified by scientists. Off the top of your head, do you know anyone who suffers from a rare disease? If you’re reading this blog post, then count me as one!

One in 12 Canadians has a rare disorder.

Approximately, 3 million Canadians and their families face a debilitating disease that severely impacts their lives.” (1)

In some cases, great strides have been made in the research and treatment of rare disorders. For others, not so much. Mine isn’t a genetic disease, nor something I was born with. My story starts off sounding like the punchline of a bad joke: In March 2016, I slipped on a patch of ice, and broke my arm.

That’s it. That’s what triggered my own rare disease, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS); a broken arm, at my right wrist. It was such a clean break that I didn’t even need surgery. The fantastic emergency room doctor at my community hospital was able to set the distal radius fracture – often called a Colles’ fracture by healthcare professionals – very quickly. One X-ray before she set the bone, another afterwards, and I was on my way home.

In the best case scenario, the story would end there. Mine, unfortunately, didn’t. Within a little while I had mysterious symptoms in my right hand and arm, but unfortunately the orthopedic surgeon who had been assigned to my follow-up care – even though I didn’t need surgery – kept dismissing my symptoms.

In effect he dismissed and disrespected me, as a person. In some ways, I still haven’t gotten over that. I’d chosen a career in bioethics, biomedical ethics, because of my desire to help patients – to help people. But there I was, now a patient myself, unable to get this specialist to even listen to me. It was a discouraging, disheartening, and infuriating period.

For almost three months, I kept going back to the community hospital to try to convince this specialist that something was wrong. It made no sense to me that I was experiencing pain that was three times worse than my initial fracture, that there were red stripes across each of my finger joints, that my skin on that hand and arm was hotter to the touch and constantly felt as though it was on fire.

It turns out that I was correct; something was indeed wrong. My simple broken arm had triggered CRPS. Although a rare disease, CRPS most commonly occurs after a Colles’ fracture, and usually in women my age. After almost five years now, it has progressed and become a debilitating condition.

CRPS causes not only constant and severe neuropathic pain in my right hand and arm, but also a long list of autoimmune and neuro-inflammatory symptoms. Some examples are adhesions that form in my wrist and finger joints like scar tissue between my joints, and full-body autoimmune fatigue.

By late 2018 a mild cognitive impairment had kicked in, from the neuro-inflammatory side of this disease, and I had to abandon my career and my dream job.

The cause of CRPS remains unknown, so there are no effective treatments. Doctors can only try to treat the symptoms, which is always difficult for chronic pain conditions. It’s a truly nasty rare disease, one that affects adults more than children:

This condition is enigmatic in nature.

It has been historically difficult to diagnose, arduous to treat, and the pathophysiologic mechanism behind its development has not been clearly defined.”(2)

CRPS is challenging for both patients and healthcare professionals, because all we can do is to try to manage its symptoms as best we can. There’s no research evidence to back up any particular type of treatment at this point, in part because each patient with CRPS may have a different set of symptoms. In effect, any given CPRS patient may have their own unique version of this disease:

complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) – multiple system dysfunction, severe and often chronic pain, and disability… has fascinated scientists and perplexed clinicians for decades”(3)

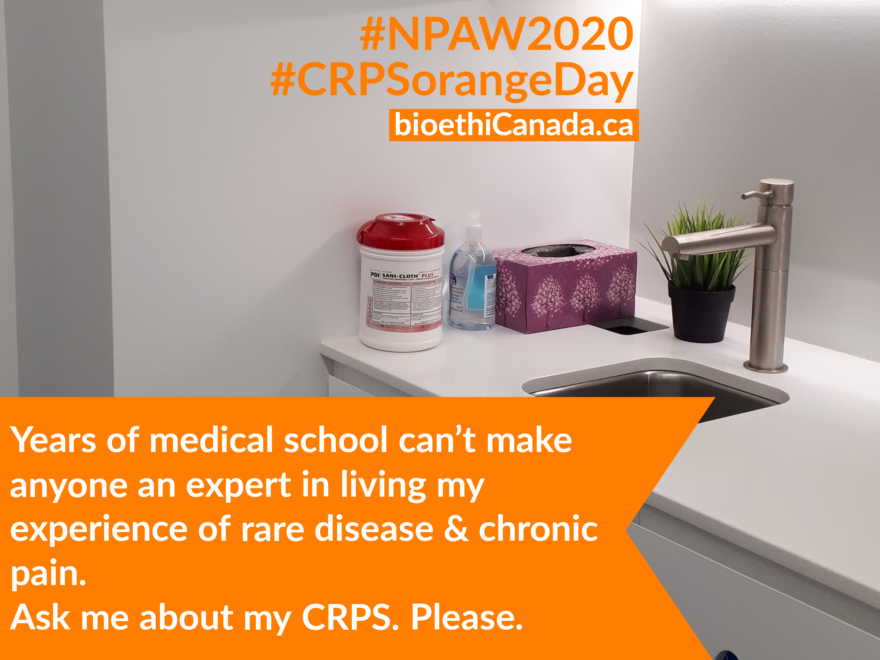

Today is CRPS Awareness Day, called “CRPS Orange Day” because the colour for this rare disease is flame orange. One of the most common symptoms is the feeling that the affected area of the body is on fire, so most CRPS organizations have a flame in their logo. The rest of this month is CRPS Awareness Month.

So I’m wearing orange clothing and raising awareness of this rare disease, in the hopes that what happened to me won’t happen to anyone else. The more people know about CRPS, the more likely it is that others will be diagnosed more quickly. A rapid diagnosis is very important in CRPS, because:

Failure to treat early may result in lifelong pain, loss of function, or even amputation; unemployment and prolonged disability are common…

Early treatment can lead to near resolution of the syndrome and the prevention of long-term pain, loss of function, and disability.”(4)

That phrase ‘near resolution’ is key; it means that CRPS will almost go away in most cases, if it’s diagnosed and treated within a window of about three months from the onset of symptoms. Can you remember how long I spent trying to convince the orthopedic specialist that something was wrong with me, after my fracture? About three months.

I have to live with knowing that there’s a strong possibility that my disease would have been much less severe if only that one doctor had actually listened to me. If only. If you’re wondering why I didn’t file a complaint against him, I did. Nothing came of it, but I haven’t had the heart yet to write about that. It’s too painful a topic for the moment.

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a life-altering condition that usually affects the extremities after a trauma or nerve injury.

The physiologic changes that occur as a result of the inciting injury are complex, as the name of the syndrome implies.

The pain and disability associated with CRPS often lead to psychological co-morbidities that create a vicious cycle of pain, isolation, and depression.” (2)

Despite my own situation, including the CRPS-related cognitive issues that stole my career from me, I feel compelled to raise awareness of this horrid disease. So many people with this disease become anxious or depressed, although I often wonder whether this is due to their pain and other symptoms or to having been disbelieved by their healthcare professionals – as I was.

In either case, it’s challenging enough to get through the day with severe pain let alone with added anxiety and/or depression. For this reason there are few patients who are able to advocate for CRPS patients in general, or to raise awareness of this rare condition.

For each of us with this disease, and for all the people who will eventually develop it, I hope to encourage healthcare professionals to learn about it and researchers to study it. One way to do that is to create images that intrigue, that pique a viewer’s curiosity; that’s what I’ve been doing, by taking a creative arts approach to the images I create for my awareness messages. Images like this one, that – hopefully – draw a viewer in and encourage them to read the accompanying text.

And that, my friends, is why I share my patient stories and artistic photography. To try to raise awareness of CRPS among healthcare professionals, so that they’ll be able to recognize it – and treat it – sooner in other patients.

As always, thanks so much for stopping by. Stay safe, keep healthy, and take time to nurture your well-being.

References

(1) Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders (CORD). About CORD: Key facts. Webpage. 2020. Accessed 01 Nov 2020. Online:

https://www.raredisorders.ca/about-cord/

(2) Shim H, Rose J, Halle S, Shekane P. Complex regional pain syndrome: a narrative review for the practising clinician. Br J Anaesth. 2019 Aug;123(2):e424-e433. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.030. Epub 2019 May 2. PMID: 31056241; PMCID: PMC6676230. Online:

https://bjanaesthesia.org/article/S0007-0912(19)30235-1/fulltext

(3) Clinical features and pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. (Review Article.) Johan Marinus, G Lorimer Moseley, Frank Birklein, Ralf Baron, Christian Maihöfner, Wade S Kingery, et al. The Lancet Neurology. 2011(10):7; 637-648. 01 July 2011. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70106-5. Online:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laneur/article/PIIS1474-4422(11)70106-5/fulltext#secd13577181e290

(4) Winston P. Early Treatment of Acute Complex Regional Pain Syndrome after Fracture or Injury with Prednisone: Why Is There a Failure to Treat? A Case Series. Pain Res Manag. 2016;2016:7019196. doi:10.1155/2016/7019196. Online:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4904610/