Long before being diagnosed with CRPS, in my right hand and arm, I was very familiar with the experience of being a patient. As a child competing in multiple sports, I’d had my fair share of injuries and emergency hospital visits. Sprains and fractures were common in figure skating, because you often fall while learning how to land a jump.

Practicing a new spin might send you careening across the ice, too dizzy to stop before you hit the boards. Not a very graceful image, I know, but I liked figure skating for its speed more than for its art.

The feeling of flying across the ice was what drew me to the rink, each morning before school. That’s probably why I still love cycling, even with CRPS, because it feels like flying.

You might expect there to be fewer injuries in competitive swimming and diving, but I went from the pool to the hospital a few times. I even managed to give myself a severe concussion, by missing a flip-turn and whacking my head against the concrete edge of the pool. Once my coach thought my nose was broken, from an elbow to my head during a water-polo match.

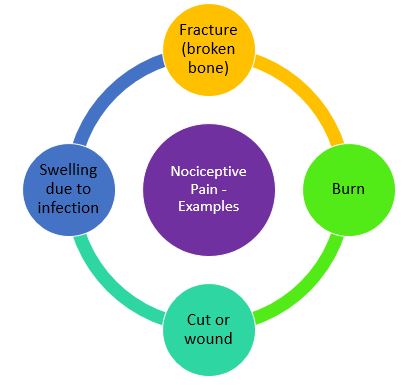

Injuries like these were simply a risk of competitive sports. As soon as your fracture or sprain healed, your coach would have you training again. Even without injury, our swim-team workouts were often brutal. We’d all be in pain the next day, but that was good; it meant that our bodies were building muscle strength.

I grew up knowing that pain was just temporary, and that sometimes it was a good thing. When I hit adolescence, everything changed. I suddenly developed what was called exercise-induced asthma. Instead of going from the pool to the hospital in someone’s car, I went by ambulance; I’d stopped breathing.

The doctors later told me that I’d been in respiratory arrest. The lifeguards had done artificial respiration, to keep me alive until the ambulance arrived. All I could remember from the asthma attack, before I lost consciousness, was agonizing pain. By the time I came to in the hospital, the pain was already gone.

Over the next few years, I was back in the hospital twice more with respiratory arrest. Each time, I experienced the same horrendous pain before passing out. At the time not much was known about asthma, so the treatments were kind of hit-and-miss. I remember specialists saying: “Let’s try this and see if it helps”…

Out of self-defence, I learned my body’s language. It could communicate warning signals through sensations or sounds; a catch in my breath, an almost imperceptible wheeze, a twinge in my chest. In sports I’d learned to ignore my body’s signals, to “push past the pain”. I still did that, for everything except the asthma, until last year.

My doctors were impressed that I was able to prevent many asthma attacks from progressing, and becoming severe. Despite that, every year or so I’d find myself back in the hospital, with an asthma attack that I couldn’t control on my own. I’d need a nebulizer treatment, or intravenous (IV) corticosteroids, to be able to breathe properly again. I got used to being a patient, to visiting different hospitals.

My asthma is still there, although it’s now well-controlled with medications. But guess what I still do, whenever I travel? I look up the location of the nearest hospital, or 24-hour emergency clinic, to where I’ll be staying. Most folks check for restaurants or attractions close to their hotels; I check for hospitals!

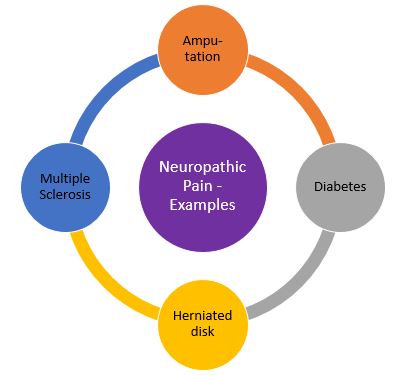

As an adult, I’ve experienced chronic pain. A herniated disk from a sports injury in my 20s. Another herniated disk, from a different sport, in my 30s. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was a regular source of pain in my 30s, until I eliminated a few foods and adopted a whole-food approach to eating.

Then I had adhesive capsulitis in my 40s. First in one shoulder, then in the other a few years later. Each of these conditions eventually got better. I even managed to get rid of plantar fasciitis (a type of foot pain), which I’m told often plagues people for decades.

When I was diagnosed with CRPS, it brought me right back to that first asthma attack in early adolescence. Another specialist, saying: “Let’s try this, and see if it helps”. Only this time we were talking about a stellate ganglion block, in a hospital’s day-surgery operating room, to try to stop the spread of the disease.

And this time, I couldn’t “push past the pain”. I’ve almost died three times, suffering agonizing pain from asthma attacks. But CRPS pain? That constant, persistent, severe sensation – often burning or freezing pain? This was a whole new category of pain, and it wasn’t going away.

It still hasn’t. A laundry list of treatments and medications has taken the edge off the pain – most of the time – but it’s still there. My hand and arm still hurt more than the broken arm that triggered my CRPS, a Colles’ fracture or snapped radius.

That’s just my day-to-day pain, though. It’s often interrupted by excruciating flares of neuropathic pain, so severe that I’ll throw up or faint. From pain. A long time ago I thought that we’d never get my asthma under control, me and my specialist physicians.

My asthma is now controlled with daily medication, and it rarely bothers me. Maybe someday we’ll all be able to say the same thing about CRPS! It’s worth hoping for, isn’t it? ‘-)

That’s one of the reasons for which I try to raise awareness of this disease, among healthcare professionals, researchers, and scientists; in the hopes that one of them will become interested enough to try to find an effective treatment!

As always, thanks for reading. Have a lovely day, and enjoy whatever happy moments it brings you; a singing bird, a beautiful flower, a laughing child…