I used to wake up with a feeling of anticipation, on the last day of February each year. In many ways it would feel like the end of a long cold Montréal winter. We’d still have snow and ice on the ground, of course, sometimes even until late April. This is Montréal, after all!

But flipping the proverbial calendar page to March meant that spring was just around the corner. Longer days, more hours of sunlight. Warmer weather, getting on our bikes outside – instead of a riding a stationary bike to nowhere, day after day.

At the end of February we knew we’d soon be seeing the green tips of the plants in our gardens, pushing up through the crust of snow. Snowdrops, then crocuses, bluebells, daffodils – all these signs of spring would soon be brightening our days.

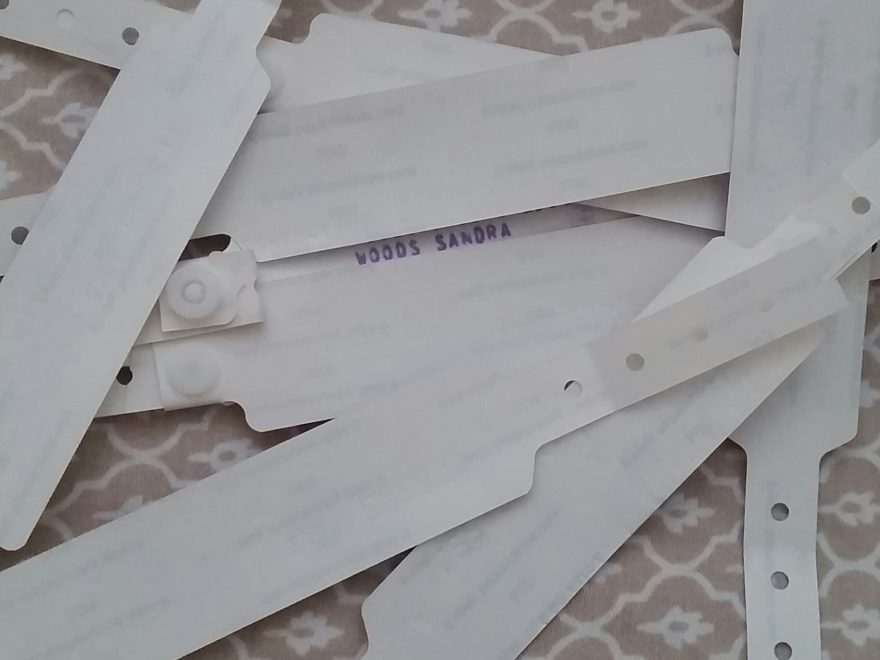

Then came March of 2016. A simple broken arm, because I slipped and fell on a patch of invisible ice. My Colles’ fracture was a clean break, snapping the radius near my wrist. This is a common fracture in this part of the world, in icy conditions, because we all tend to instinctively put our hand out to break a fall. I drove myself home, with a visibly broken arm, because it would have taken much longer to have my husband come pick me up and then drive back to the hospital near our home. So, as I said at the hospital, I can “deal with temporary pain”.

I even stopped to pick up a coffee for my husband, because it was late evening and I knew that he’d be almost asleep by the time I got home. I wanted him wide awake, to help me – very carefully! – change out of my favourite work clothes (because I didn’t want them ruined by plaster dust from a cast) and then drive me to the hospital. Having worked in a hospital myself for several years, I know better than to let him drink the coffee in the emergency area waiting room!

That broken bone didn’t even require surgery, and I was set up with an old-fashioned plaster cast at a local community hospital. Even though we didn’t get home from the hospital until well past midnight, my husband and I were both back at work early the next day. We didn’t even get my prescription filled, for some mild pain medication, until lunchtime that day. The hospital pharmacy closes at midnight, so the doctor there wasn’t able to provide me with any pain medication to bring home; all I had was the injection when she had set my fracture.

It was a point of pride with me that I never missed any time at work, and when I had a medical appointment I’d always work late – or go in early – to make up the time. Part of that was also because I loved my job!

Within 10 days of that fracture, though, I knew that something was wrong. I’d had broken bones before, mostly from sports injuries, so I knew that the pain would start to lessen after a few days. I expected my pain to level off, to a dull ache. Instead, my pain changed – and became much worse – in several different ways.

By about 10 days after I broke my right arm, it would suddenly feel as though someone was running electrical currents through my arm, from just below the shoulder to my fingertips. Well, what I imagined an electric current would feel like. My entire body would twitch, from that feeling of electric shocks running through my arm.

There was also a constant feeling that my fingertips were on fire. That they’d been soaked in gasoline, and then set ablaze. I’d get up several times during the night, every night, because it felt as though the skin on my fingertips was burning and blistering. Soaking them in tepid water would at least reassure me that the tips of my fingers couldn’t actually be burning.

After a few days of this, I returned to the hospital’s emergency department. The doctor there couldn’t see any additional injury on a new X-ray, so suspected that my cast might be too tight. A partial opening was cut into my plaster cast, which was then taped back up a bit more loosely. I was told to that if the symptoms didn’t get better, I should wait for the follow-up appointment with the hospital’s orthopedic department – that they should call me soon for an appointment as a follow-up to my initial hospital visit for the fracture.

When I asked whether I could begin post-fracture physiotherapy right away, the emergency doctor asked why. I explained that my work in bioethics required a lot of time on a computer keyboard, and also that I’m right-handed so wanted to be sure that I didn’t have any long-term issues from this fracture. I also mentioned that our too-short cycling season would soon start, so I wanted to be ready to get out on my bicycle as quickly as possible after the fracture had healed.

My goal was always to get back to my normal as quickly as possible, to continue being active and pursuing the outdoor sports that I’d always loved. Mostly alpine hiking and snowshoeing, along with local canoeing, cross-country skiing, and cycling. And swimming in a nearby lake, although less often than the other activities because my sweetheart isn’t fond of the water – except in our canoe.

Before I left the hospital emergency room, after my cast had been loosened, the doctor agreed that I could see a physical therapist and said that this might even help with my pain symptoms. I went home believing that I’d start to feel soon, now that the cast had been loosened; that all my painful symptoms had been because my hand had swollen up inside the cast, making it too tight.

The looser cast made no difference whatsoever. I waited, in excruciating pain, for the hospital to call for my post-fracture follow-up appointment. I didn’t know it at the time, but I’d been assigned to an orthopedic surgeon even though I wouldn’t need surgery… simply because he was the ‘next in line’ for a follow-up patient referral from the hospital’s emergency department.

As a bioethics note, this is one of the many failings of our public healthcare systems in Québec; instead of reserving the time of orthopedic surgeons for people who actually need surgery, patients are randomly assigned to members of the orthopedic department based on who’s ‘next in line’ to receive a referral.

Meanwhile, my symptoms continued to worsen. The burning sensation in my fingertips had spread a bit further up my fingers, and my fingers were starting to feel stiff. I was in so much pain that I could barely focus on my work, and started to vomit from the intense pain. Trust me, that’s really no fun – particularly when you work in a carpeted office building!

I took to carrying extra-large zip-top plastic freezer bags in my pockets, so I could discreetly vomit into a bag and then seal it before putting it in the trash. And I stopped eating, during working hours, to that only liquid would come up. I called the hospital, to ask about my follow-up appointment with the hospital’s orthopedic service, and was told that they’d lost my referral – between departments at the same hospital.

Here’s another believe it or not bioethics note; the hospital asked me, the patient, to fax the carbon copy – yes, we were still using carbon copy forms in Québec hospitals in 2016! – of the referral slip from my initial emergency visit to the orthopedics department. And they asked me to then call the orthopedics service directly to ensure that they had received my fax. Luckily I had access to a fax machine at my office, so could do that immediately.

When I finally went back to the hospital for that post-fracture follow-up visit, I was in agony. I expected to find out why I was in so much pain, and to discuss a treatment plan of some sort. My husband had wondered whether I’d need surgery, for example, or whether the snapped ends of the bone might have been misaligned. Instead, the orthopedic surgeon was dismissive and even disrespectful.

And so it went, for months. I continued vomiting from the intense pain of that sensation of electric shocks in my hand and arm, and started passing out from pain – at the office. I was afraid to drive, in case I fainted from pain while at the wheel; I was terrified that I could hurt someone. But the surgeon wouldn’t listen. Weeks went by, appointment after appointment he simply dismissed my symptoms.

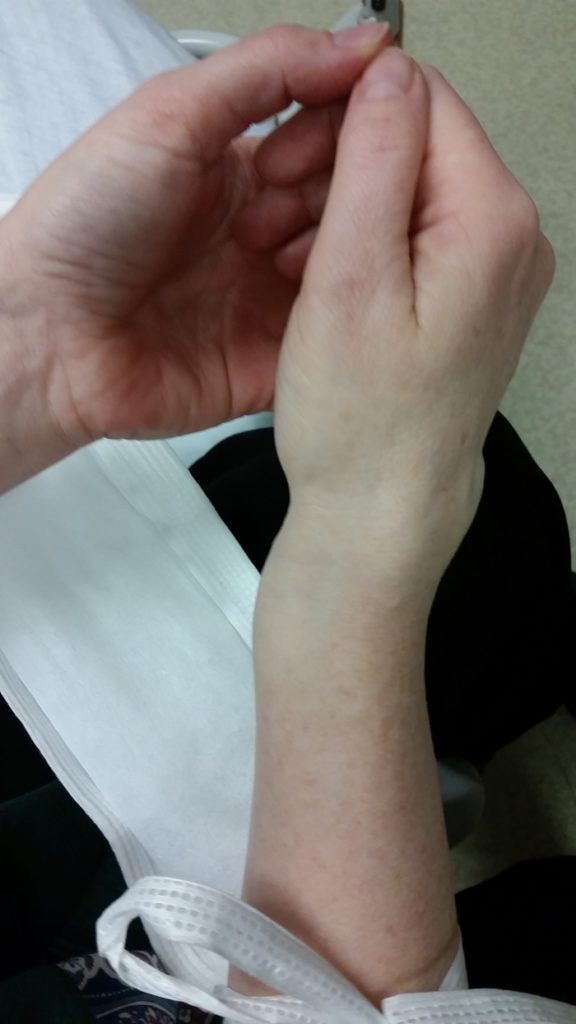

The symptoms kept creeping up my fingers and my knuckles all became stiff, as though they were blocked in some way; they wouldn’t bend even if someone tried to bend them. Red stripes formed across each row of joints on my right hand, and the skin there was often red and hot to the touch – as though I’d gotten a bad sunburn.

But still, still, this orthopedic surgeon dismissed all this. If you’re wondering why I didn’t simply get a second opinion, I tried to. It took almost three months to finally get a second opinion, because the hospital kept refusing my requests for one. They refused my requests for another referral, or even to change my follow-ups to another orthopedist.

[I later made a complaint to the hospital, which resulted in an internal investigation, and the practice of blocking these types of patient requests was stopped; it had been a directive from the orthopedic surgeons to their departments administrative personnel, and went against the hospitals Charter of Patients’ Rights.]

Earlier on in this post I wrote: “Within 10 days, I knew that something was wrong” after I broke my arm. Well, it turns out that I was correct. Something was indeed wrong, and that 3-month delay – while I waited for that orthopedic surgeon to listen to me – would have been a crucial period for a good recovery.

I had developed Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), which had been triggered by my Colles’ fracture. CRPS is considered a rare disease, but one of its most common triggers is precisely that type of fracture. Its most common symptom? A sensation of burning pain in a hand or foot, after physical trauma; a fracture, a compression injury such as a car accident, even surgery.

All along, during that entire period, I had the ‘classic’ symptoms of CRPS, after one of the most common ‘inciting factors’ for this condition; that particular type of fracture. Another known trigger for CRPS is surgery, specifically to the limbs – a person’s arms or legs.

So in my view, the orthopedic surgeon should have recognized that there was a possibility that something really was wrong, instead of repeatedly dismissing my symptoms, and dismissing me as a patient.

I later found out that if CRPS is aggressively treated within its first 3 months, it will often resolve. It can go away, if diagnosed and treated quickly. Instead, an orthopedic surgeon wasted those three months, by ignoring my reports of intense pain, of burning sensations, and all the other symptoms of CRPS.

This disease has completely changed my life. The pain is a constant feature of my days now, although it is thankfully a bit less severe after several series of medical procedures in different hospitals:

. 6 stellate ganglion blocks

. 2 Bier blocks

. Numerous axillary brachial plexus blocks

. Several full-body infusions of medications (the same basic process as chemotherapy)

. Years of excruciating and expensive physical therapy treatments

Then there are the neuro-inflammatory aspects of this disease. CRPS is an extremely odd condition, in that it’s considered to be both an autoimmune disease and a neuro-inflammatory condition. On the neurologic side, cognitive issues develop in approximately 65% of patients who have this disease for more than a few years:

Significant neuropsychological deficits are present in 65% of patients, with many patients presenting with elements of a dysexecutive syndrome and some patients presenting with global cognitive impairment.” (1)

That research used “tests that assess executive control, naming/lexical retrieval, and declarative memory” (1) Executive control, in neurologic terms, includes thought processes like planning and problem solving. The category of naming/lexical retrieval is the ability to remember words and to use them properly.

That final category, declarative memory, is usually broken down into ‘episodic memory’ and ‘semantic memory’. As you’ll see from the quotations below, these types of cognitive activities are a large part of what make each of us our own unique selves:

Episodic memory involves the ability to learn, store, and retrieve information about unique personal experiences that occur in daily life.

These memories typically include information about the time and place of an event, as well as detailed information about the event itself.” (2)

Semantic memory, on the other hand, is rooted in our ability to use language, to understand theories, and to express concepts:

Human beings have the ability to represent concepts in language.

This ability allows us not only to disseminate conceptual knowledge to others, but also to manipulate, associate, and combine these concepts…

humans use conceptual knowledge for much more than merely interacting with objects.

All of human culture, including science, literature, social institutions, religion, and art, is constructed from conceptual knowledge…

Activities such as reasoning, planning for the future or reminiscing about the past depend on the activation of concepts stored in semantic memory” (2)

Why am I spending so much time focused on these cognitive issues? Because at the end of 2018 I was diagnosed with a mild cognitive impairment as a result of my CRPS. This limits my ability to concentrate or focus on anything for more than an hour at a time, including discussions, meetings, reading, or writing. It makes it almost impossible, at times, to plan or to think things through long-term, or even to express myself properly.

These activities formed the basis of my work in bioethics, so I was forced to abandon a career that I adored – at least 15 years earlier than I’d have ever considered retiring. I’d only recently landed my dream job, a newly-created position that fit me like a glove, so it was heartbreaking to have to step away.

I’d also begun, soon after my diagnosis with CRPS in 2016, to use my bioethics training to raise awareness of this disease among healthcare professionals. Why not focus my awareness efforts on patients?

Because the key, in my view, is to make doctors, nurses, and other health professionals aware of these specific symptoms so that they can recognize CRPS and more quickly refer patients to specialist care. To hopefully help patients obtain treatment within that 3-month window, for the best possible outcomes. So that others don’t end up with the life-changing impacts of this rare disease, that I have to live with every day. Symptoms that have changed my husband’s life, as well, along with all of our retirement plans.

The last day of February each year now holds a completely different meaning to me, because it marks international Rare Disease Day. There are an astounding number of rare diseases, and mine is just one of them. According to The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), there are now more than 7,000 known rare diseases, which impact more than 300 million people around the world. (3)

Thanks so much for taking the time to read about CRPS, so that someday you might be able to recognize it in someone else and help them get the medical help that they need.

References

(1) Libon, David J, Schwartzman, Robert J, Eppig, Joel, et al. Neuropsychological deficits associated with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J International Neuropsychological Society (JINS). 2010; 16, 566–573. Online 19 Mar 2010. doi:10.1017/S1355617710000214. Accessed 28 Feb 2022:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-international-neuropsychological-society/article/neuropsychological-deficits-associated-with-complex-regional-pain-syndrome/F56D83F23BB269C52DDF43198BA0536D#

(2) Camina, Eduardo, and Güell, Francisco. The Neuroanatomical, Neurophysiological and Psychological Basis of Memory: Current Models and Their Origins. Frontiers in Pharmacology (Front. Pharmacol.). 2017; 8. Online 20 Jun 2017. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00438. Accessed 28 Feb 2022:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2017.00438/full

(3) The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). About Rare Disease Day. Webpage. Undated. Online. Accessed 28 Feb 2022:

https://rarediseases.org/rare-disease-day/