There are two different stories that I’d really like to write about tonight, but it’s late. I just got back from an appointment with my family physician. One of the stories I want to tell is something that made me very happy, and the other isn’t. So tonight I’ll write the happy tale, and keep the other for another day.

If you’ve been following my patient journey, you might recall that I recently did a presentation to second-year medical students at McGill University. That was back in early February, as a co-presentation with the Director of the Alan Edwards Pain Management Unit (AEPMU) at which I’m a patient.

These medical students were visiting the AEPMU patient clinic for a half day, as part of their medical education (MedEd), because the AEPMU is part of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC). It’s a world-class chronic pain centre, with two different arms; a patient care clinic, and an affiliated pain research centre.

I’ve been a patient at the AEPMU since 2016, for a disease named Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), often still called Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD); its former name. My disease is a good one to present to medical students, for several reasons.

First off, CRPS is considered to be one of the most painful of the many chronic pain conditions. Next, is has a long list of potential signs and symptoms. Then there’s fact that each patient presents differently with CRPS. That means that any two patients may have different sets of symptoms, so there’s not really one standard treatment plan for this disease.

It’s also a good discussion topic for medical students because very little is known about the etiology of CRPS; what its underlying cause – or causes – are. Or which factors might make certain people more susceptible to this disease than other individuals.

This condition is also considered to be relatively rare, although certain injuries are more often associated with CRPS. That includes the type of broken arm that triggered my CRPS, from slipping on a patch of winter ice.

A Colles’ fracture occurs when the radius breaks very close to the wrist; what you or I would probably call a broken wrist. CRPS also has a reputation, among physicians, as being challenging to treat. Overall,

CRPS is recognized as one of the most difficult conditions to treat among pain syndromes.”(1)

I can confirm that it’s also extremely difficult and challenging for patients to live with! It’s so hard to deal with, in fact, that research has shown a suicidal ideation rate of up to 74.4% among CRPS patients.(1)

Put another way, that means that up to three out of every four CRPS patients consider suicide – due to this disease. I suspect that part of this may be because it often takes a long time to get a diagnosis of CRPS, and all the while some healthcare professionals react with disbelief to the pain levels experienced by patients:

Patients often recognize early on, that a minor injury has become complicated by inappropriate pain and disability. These patients are frequently dismissed as neurotic until the signs of RSD are well advanced.”(2)

This is one of the reasons I write about CRPS, and do patient advocacy and outreach activities. My goal with this is to help raise awareness of this condition, particularly within the healthcare community, so that other patients can receive a diagnosis more quickly in the future.

It’s also why I’m always happy to talk about CRPS, whether on this blog, on social media, at public events, or during presentations. I’ve even used an art exposition to raise awareness of this nasty autoimmune and neuro-inflammatory condition!

What does all this have to do with my appointment tonight, with my family doctor? As soon as I went into the examination room, I saw two young men sitting in a corner. My doctor is truly interested in training the future generation of physicians, so he often has medical students shadowing him.

They spend a day with him, as a kind of on-the-job-training, to learn how to interact with all different types of patients. It’s an opportunity for them to see first-hand the variety of conditions for which people visit a family medicine doctor.

This is important, because a family physician is often the first medical professional that any patient will see in Canada – except for emergencies like car accidents, of course! I looked at my doctor, and said “Medical students, right?”

He just laughed, and told me that I could introduce myself to the students – instead of him doing it – because he knows that I’m not shy. Did I say that my doctor has known me for a while?!

Then I asked my doctor if he had any paperwork (data entry, really) to catch up on – he always does. When he said yes, I offered to do a 5-minute mini-presentation on my disease to these medical students; while he did some administrative work.

He liked that idea, and told me that he’d be listening in as well – in case he could learn anything new from me about CRPS. Or in case he needed to provide more information to the students.

Then he told his two young trainees not to be surprised if I spoke to them as a professor would, because I’d worked in healthcare for years – in bioethics, in clinical research, and in hospital.

Those comments, from my own family doctor, were enough to make me very happy tonight. But this story doesn’t end there; it gets better ‘-) I turned my chair to face the two students head-on, and asked whether they’d ever heard of CRPS or RSD. One said no, and the other shook his head.

I started with this, my usual quick introduction to CRPS – for healthcare professionals and trainees:

CPRS is considered to be a rare condition.

Until recently it was thought to be solely a neuro-inflammatory disease, but recent research has found inflammatory markers.

This is why it’s now thought to be both an autoimmune and neuro-inflammatory disease…”

Before I was able to finish that second sentence, both of these young men had pulled their notepads out of their chest pockets and had started taking notes.

I stopped – to let them catch up! – and then asked how many pages they’d each written in their note pads today, after meeting with other patients. They looked up somewhat sheepishly; one said “not much” and the other “barely anything”.

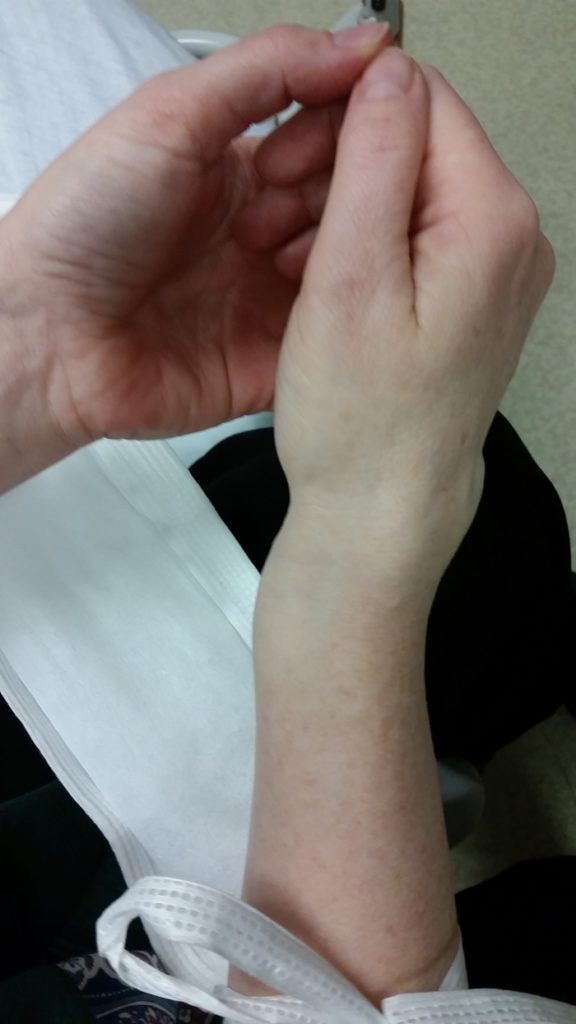

And that’s what really made me happy today. The fact that these two medical students were so genuinely interested in this disease that they started taking notes, literally the moment I started discussing it. I even had some photos to show them, on my phone; the broken arm that triggered my CRPS, even the X-rays of the fracture.

After I finished my little impromptu presentation, they had some excellent questions about CRPS. They were particularly concerned about the importance of rapid diagnosis and treatment, to prevent the disease from spreading, becoming entrenched, and potentially permanent.

Which is what happened in my case. Luckily I was able to answer all of their questions, and also to refer them to some medical journal articles which would give them more information on CRPS. I keep some of these saved on my phone, for whenever I get the chance to talk with people in healthcare about this condition.

By this time my doctor had finished hammering away at the keyboard of his computer, so I could tell that he was ready to start our actual appointment. And that’s what I’ll write about – another day.

As always, thanks for reading, and feel free to comment on social media. If you’re a regular follower, you know how to find me!

References:

(1) Lee, Do-Hyeong et al. “Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation among Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome.” Psychiatry investigation vol. 11,1 (2014): 32-8. doi:10.4306/pi.2014.11.1.32. Web: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3942549/

(2) Hannington-Kiff, J.G. “Intravenous Regional Sympathetic Blocks”. Chapter 12 in “Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy”, page 123. Eds. Stanton-Hicks, Michael, Jang, Wilfrid, and Boas, Robert A. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Boston. 1990.